Ep 3: The Second Ed-Tech Revolution

This is Episode 3 of the series that I am writing to demystify Ed-tech for anyone outside the system.

D-day

0500 hrs, Hostel 8, IIT Bombay. Hubble almost fell over on his laptop as he frantically punched the keys on it.

'Hubble' was one of our co-founders. I will call him Hubble because he loved telescopes and stargazing. I could also call him Skinner due to his weird infatuation with pigeons, but more of you know about Hubble than about Skinner, so Hubble it is.

Hubble and I hadn't slept for 2 days. Heck, we hadn't slept for more than 4 hours per day for the last 2 months. Coffee wasn't strong enough, and Redbull no longer gave us wings - we could have slept with a constant stream of cold water hitting our faces. But, we couldn't.

The teacher will be in the class at 4 pm and she has to have something to teach. That something, our product, was still a work in progress. But we couldn't keep making it till 4 pm and send it last minute - how would she prepare? The product had to be delivered to her at least 2 hours beforehand, before 1400 hours.

0600 hours. Hubble and I were still punching keys, wobbling over our laptops, about to fall over at any time, cursing the slow internet connection. The content for the first few classes was already made - the lesson plans, the exercises, the printouts, and the in-class props, were all ready to go. So, what were we doing at this ungodly hour?

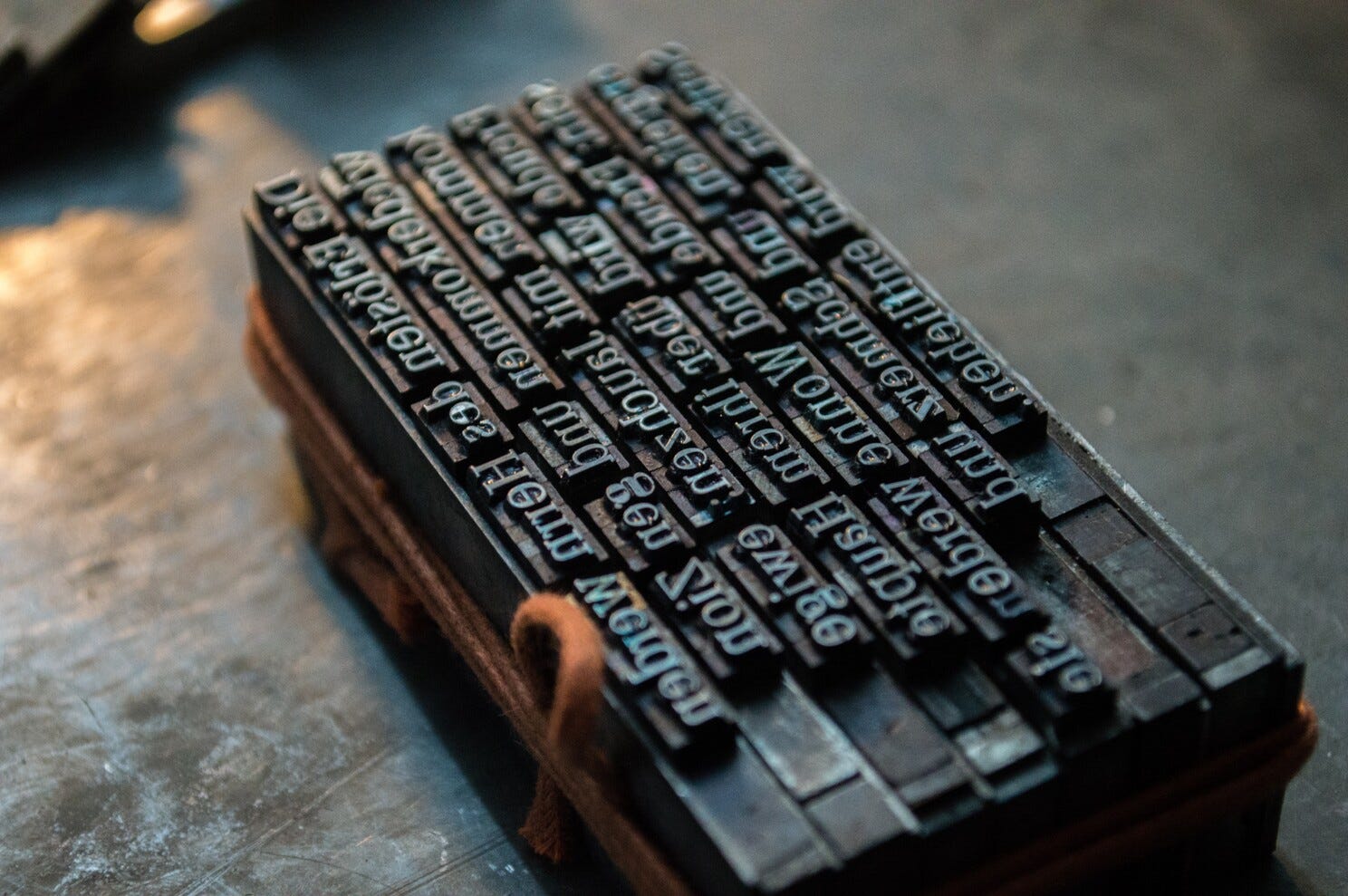

We were converting this -

into this -

Letter by letter. Word by word. Line by line. One punctuation mark at a time. But why? Why convert a perfectly good-looking doc into this gibberish? Couldn't we have just sent the content to teachers, as it was? Maybe, we could have. But there is more to it than what meets the eye. To understand it, let's go one step deeper into the world of the Ed-tech business.

Pythagoras to Gutenberg

Two out of three parts of the Ed-tech business - Ed and Business - are almost as old as humanity itself. Ed part has existed since the time humans realized that some of them were more knowledgeable/skilled than others and then decided that it would be best for everyone to share this knowledge.

As for business, the history is a bit complicated but very old. Humans have always competed for what goes into young brains and how. Teachers have always competed with other teachers, and schools with other schools. Initially, the competition was literally a matter of life and death. Pythagoras, the triangle-theorem guy who lived around 500 BC in Greece, some 2500 years ago, was a successful teacher of his time. He was almost killed by a rival for a disagreement over the 'content' of the education he imparted. Socrates, another teacher, was executed for the same reason - his 'content' was unacceptable to other teachers and his own state.

Luckily, such violence decreased over time and people needed other ways to compete. In competitive environments, violence (aka. war), is usually replaced with trade/business. Since teachers could no longer kill other teachers, they competed with their offerings - their content and their methods. Business flourished.

What about the third part - Tech? The Tech is NOT new either. It's true that Pythagoras couldn't record a video to explain his theorem and stream it to children around the world, across time periods. He, however, could write to educate others. The 'Tech' in the Ed of his time was writing. But the tech of writing had a problem, it wasn't 'scalable'.

Pythagoras' writing couldn't reach many people, because, during his time, writing couldn't be easily replicated. The only way to copy a text was to copy it by hand. In addition, people who could write were rare, and therefore the whole process became costly. If you were an upper-class Greek living in Pythagoras' time, affording a book would be uneconomical. If you were a class below that, an impossibility.

Let's say, somehow you could find 1000 customers to buy a book, you wouldn't be able to find so many copiers to copy the book by hand. The system of producing books broke down as the size of the production increased.

In all, Pythagoras' words couldn't travel far. But, that changed with the invention of printing.

Around the year 1440, almost 2000 years after Pythagoras, a German named Gutenberg invented the printing press. Now, one could write a book, send it to the press and get copies made. In Startup-speak, the printing press made writing 'scalable'.

As one 'scaled' -- Startup-Speak for 'increased the size' -- of the whole operation of printing books, the system wouldn't break. For example, if a customer wanted 1000 copies of a book, Gutenberg could create a whole workshop with multiple presses. If Gutenberg wouldn't, someone else who saw an opportunity would. By the year 1500, 60 years later, there were at least 1000 print shops in the world. Before the year 1440, the total number of printed books in the world was in the thousands. 60 years later, this number was 20 million i.e. 2 crore. This level of scalability was unprecedented, but that wasn't all.

The core innovation behind the printing press invented by Gutenberg was 'the movable type'. The whole press was essentially a giant rectangular stamp fitted with 'metal letters' - called type - that could be moved around and swapped in and out. Printing with it had some initial time investment - one had to carefully arrange letters to be printed on each page - letter by letter, word by word, line by line, one punctuation mark at a time. But, once you had arranged the letters for a page you could print that page, any number of times. It did not matter if you printed 1 copy or 100 copies of that page.

Let's say you had to print 100 copies of a page. The work required to set the letters to print one page was greater than the work required to write one page by hand. But printing the next 99 copies was much much faster, and cheaper - ink, stamp, repeat.

This meant that the per-book printing cost became cheaper and cheaper as one printed more and more copies of a book. The printing wasn't just scalable, it became cheaper as the size of the whole operation increased. In Startup-speak, printing gave writing 'the economies of scale'.

Cheaper books meant, more people could buy them and therefore more people could read them. When more people read books, they educated themselves more. Ideas spread, thinking changed, behaviors soon followed and groundbreaking discoveries were made.

If you define an Ed-Tech Revolution as Tech revolutionizing Education, then it is safe to say that - the "Tech" of the printing press, revolutionized education 5 centuries ago, in what can be called the first Ed-Tech revolution - The Renaissance.

The Second Ed-Tech Revolution

On D-day, in that hostel, 500 years after the printing press, when we were furiously punching those laptop keys, we were doing something very similar to Gutenberg. We were just like one of the printing houses but in the second Ed-tech revolution. Our printing press, our tech, was ' internet + computers'. History doesn't repeat, it rhymes.

So, why convert the doc into gibberish? Once the content on our doc was converted to gibberish - the code - it could to uploaded to a server - our website/app - through the internet. Once that was done, anyone around the world with a computer could go to our website, log in and instantaneously access a copy of the content we made. The tech made our content scalable and since making more copies cost almost no money, it had economies of scale. Adding 1000 teachers, no problem. Adding 1 million new students, no problem. Any press, even today, would break if asked for a million copies in a day, but our tech wouldn't. The scalability of this tech was boundless. But essentially, all we were doing that morning was arranging the letters and words so that cheap copies of the doc could be made, just like the press.

Our copies were a bit different from the ones Gutenberg made - they weren't just cheap they were dirt-cheap, and they were way better. Also, the tech allowed us to customize, track, and monitor our copies. In principle, that is the promise of Ed-techs - to give children cheap access to personalized content, help them track their progress, and let their parents monitor this process.

D-day. 1230 hrs. The conversion of the doc to code was done. The content was uploaded to the website and the notification was sent to the teacher. We were done an hour and a half before the deadline. We were happy. Finally, some sleep. Hubble and I crashed.

1530 hrs, 30 minutes before the class.

"Wake up! Wake up! The teacher is calling," our founder yelled and kicked me at the same time to wake me up.

I picked it up and she screamed, "What have you guys sent me? I just saw it. I am NOT using this lesson for the class. We will talk later. In the evening." She hung up.

.............Shit! What now?

Thanks for reading.

A Like or a Share will go a long way :)

Extras:

All tech does, is decrease the time or effort required by humans to do something. In other words, it makes things easier. A human can do more with technology than without technology. If you think of money as just an imaginary standard to measure human time and effort, then any technology that makes things easier or faster will make things cheaper. When things get cheaper, more people can access them and when more people can access something, it fundamentally changes their behaviour. When the technology is innovative, the speed of this change in behaviour is unprecedented, and this unprecedented change is termed a revolution.

Further Reading/Viewing

Video: How a Gutenberg press works

Book: The Gutenberg revolution by John Man